A Spectrum of Change: Why Is An Art Foundation Tackling Mass Incarceration?

/Photo: Joseph Sohm/shutterstock

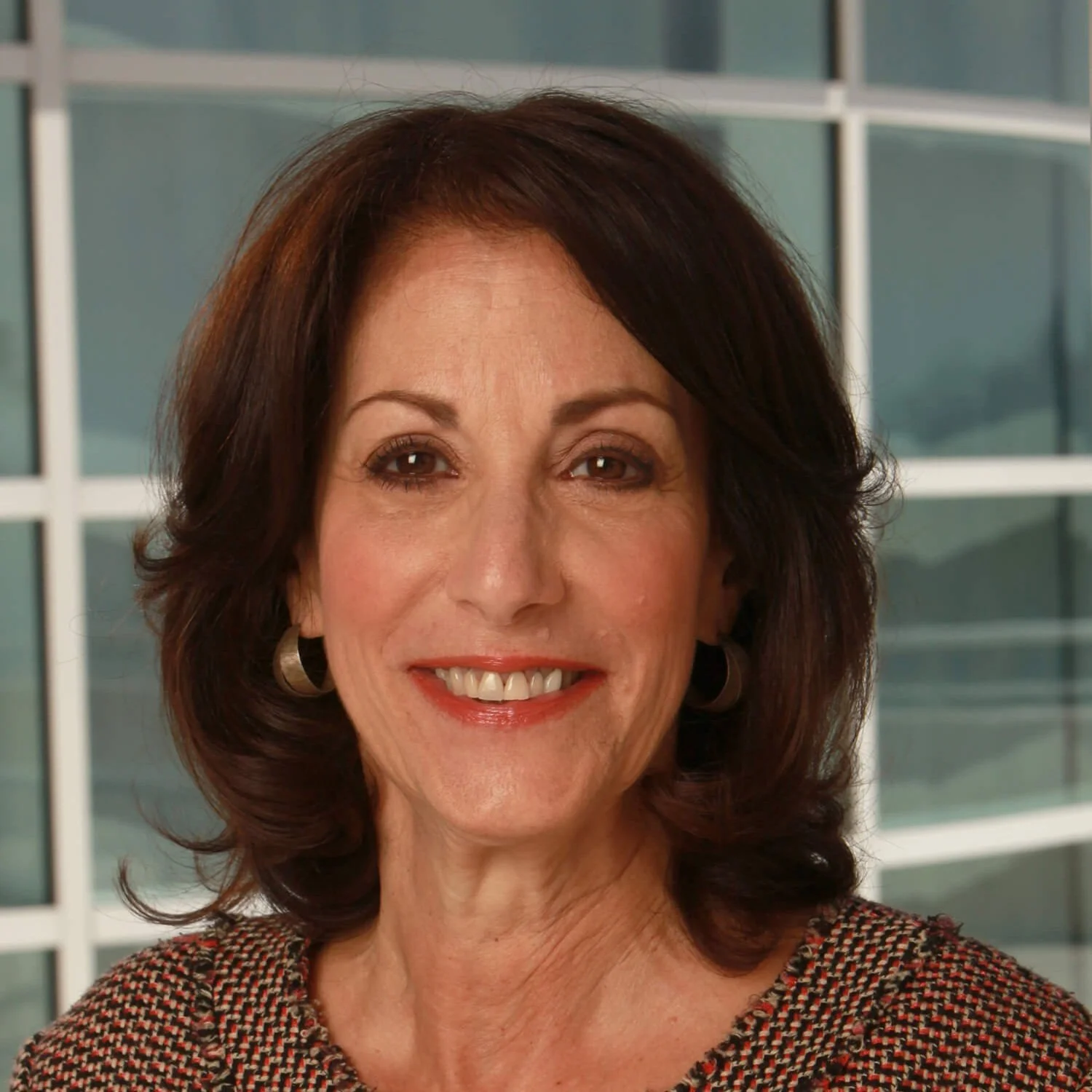

In late September, the New York City-based Robert Rauschenberg Foundation tapped Kathy Halbreich, who currently serves as Associate Director of the Museum of Modern Art, as its new executive director.

Halbreich "brings to the foundation more than 30 years of experience leading cultural institutions, a fundamental belief in the power of artists to catalyze social change, and a deep commitment to the role artist foundations can play in expanding opportunities for cultural conversation," reads the foundation's press release.

It will be interesting to see where Halbreich takes the foundation, which has carved out quite a niche for itself in recent years, particularly in the area of catalyzing social change.

A Social Change Early Adopter

In addition to supporting artists in the many fields in which Rauschenberg worked, the foundation has taken the lead in the evolving and red-hot field of "artist as activist" philanthropy, launching its Artist as Activist program in 2012.

A growing number of foundations, including A Blade of Grass, the Surdna Foundation, the Shelly and Donald Rubin Foundation, and the Ford Foundation, are working this same terrain, sharing Rauschenberg's vision that the arts can be a powerful vehicle for social change.

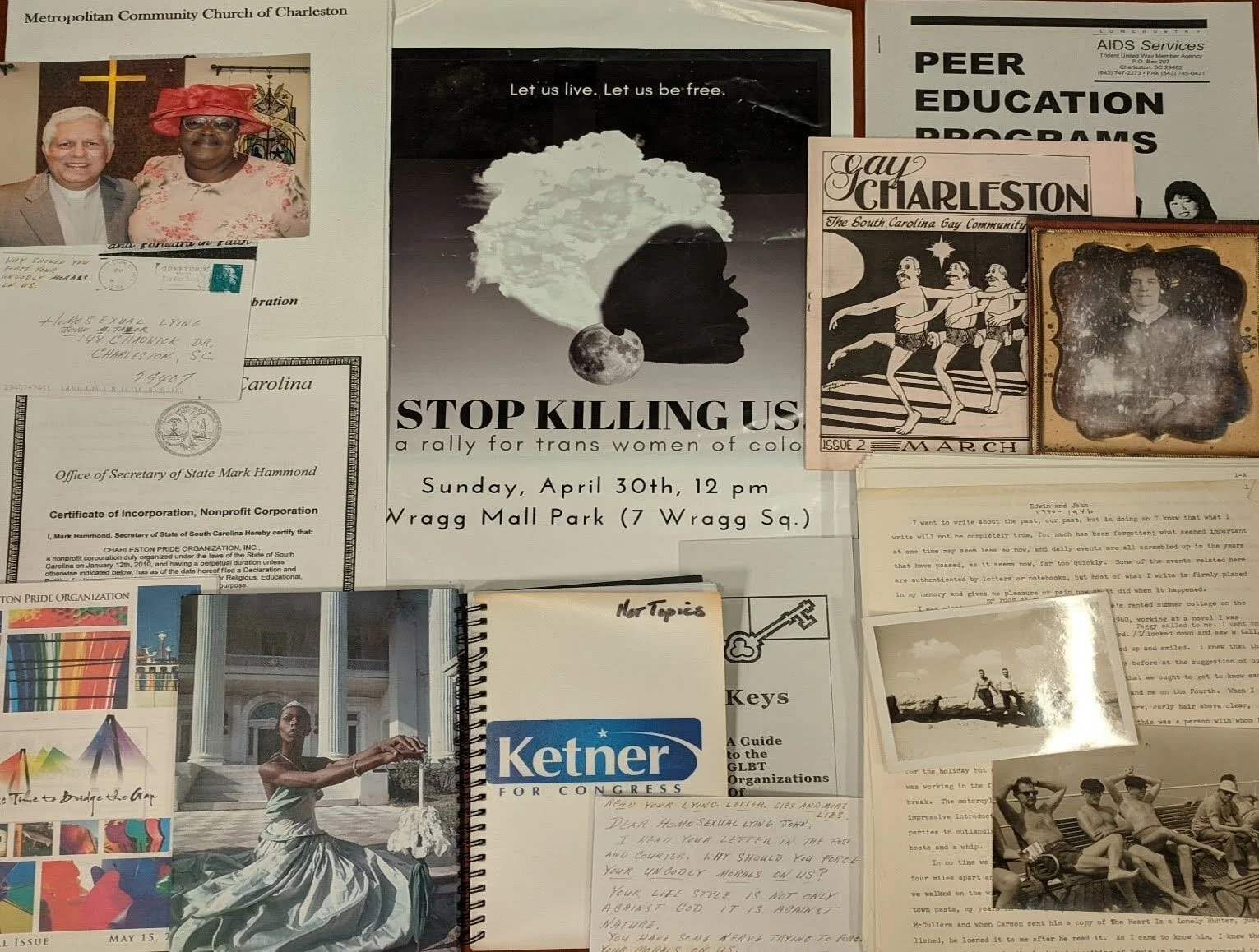

The Rauschenberg Foundation, meanwhile, has become more laser-focused in its approach. Last year, it announced its Artist as Activist program would focus solely on projects that "address the intersections between race, class and mass incarceration." By focusing on a specific issue, the foundation differentiated itself from a growing space filled with funders concerned with the broader connections between art and social activism.

But others in the art world have since come to pay new attention to criminal justice issues. Carnegie Hall has backed an initiative in this area and and the wealthy collector Agnes Gund sold a Roy Lichtenstein painting to underwrite a new criminal justice reform fund that the Ford Foundation will manage.

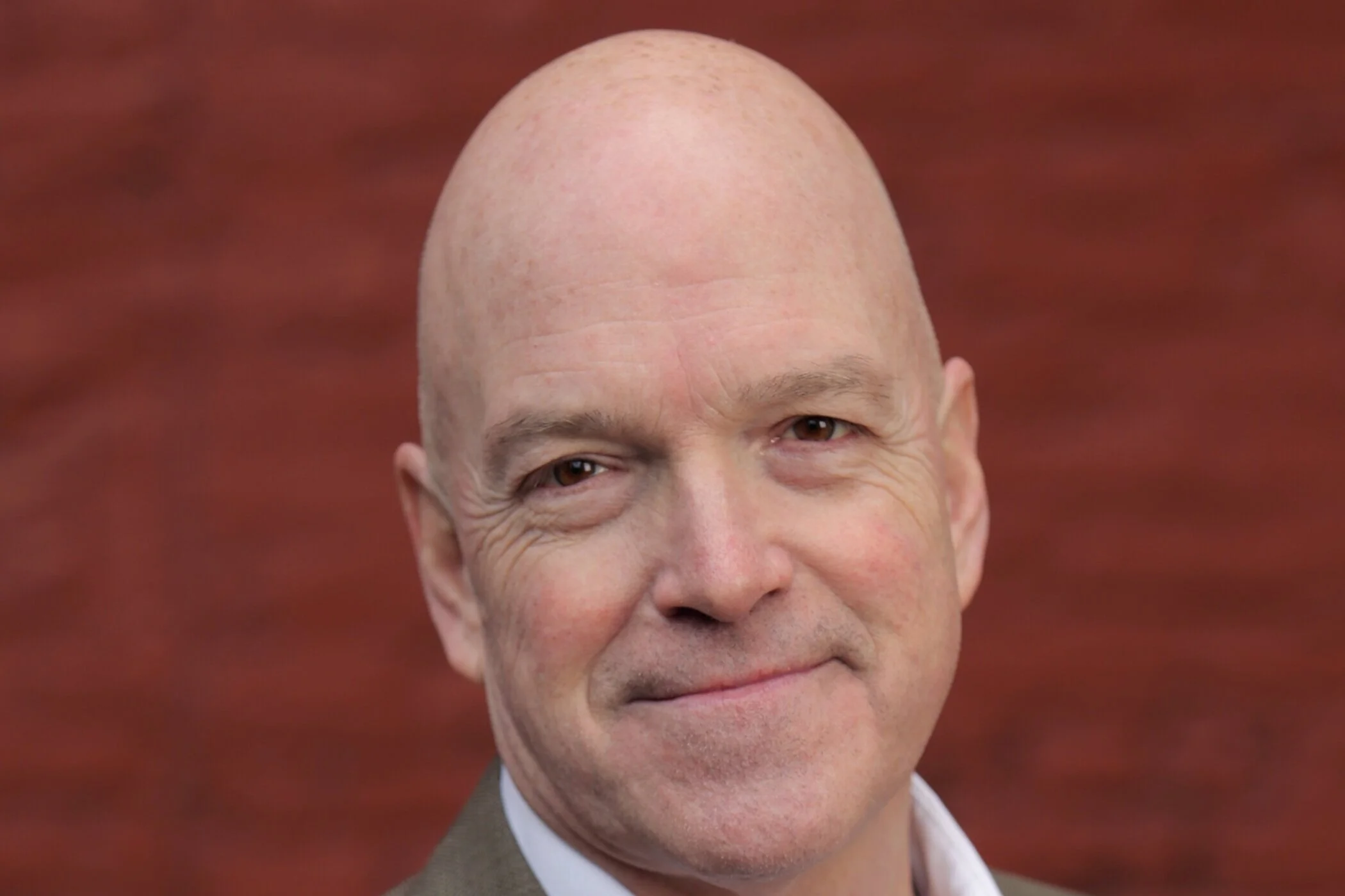

In July, the Rauschenberg Foundation awarded a total of $700,000 to its nine 2017 Artist as Activist Fellows focused on addressing "the prison-industrial complex and mass incarceration in the United States." Recently, I had the opportunity to connect with Risë Wilson, Rauschenberg's director of philanthropy, to talk about the foundation's pivot, its strategy for affecting change, and where the program is heading.

Here's a recap of our discussion.

A "Through-Line" Across Social Challenges

I first asked Wilson about Rauschenberg's pivot to mass incarceration. What confluence of factors drove this decision?

"The foundation’s leadership expressed concern for a number of issue areas—from poverty and economic justice to housing and homelessness," she said, and mass incarceration is a "through-line across each. And it is people of color and the poor who have been disproportionately criminalized and funneled through the system of jails and prisons."

In previous posts looking at funders' growing interest in reducing mass incarceration, I floated the idea that its resonance may, at least in part, be rooted in the fact that its success can be effectively measured. The "arts experience" is famously ambiguous, but there's nothing subjective or nebulous about reducing the prison population.

For example, when announcing its program to reduce youth incarceration, Carnegie Hall's press release noted that "while youth incarceration rates have declined by almost 50 percent since 2003, the U.S. still incarcerates more children than any other nation, with a youth incarceration rate five times that of the next-highest country."

Funders, in other words, seemed constitutionally wired to think quantitatively, and understandably so: It's nice to know what you're getting for your money, even if we can all agree that certain things can't be measured.

Yet, according to Wilson, "metrics were not the foundation's motivation" in explaining Rauschenberg's pivot. Rather, "the experience of the people being incarcerated, the experience of their children and loved ones, the urgency and salience of this issue were the drivers."

Where Small and Large Funders Intersect

I then called attention to the fact that slowly but surely, large legacy arts organizations and patrons are coming around to Rauschenberg's way of thinking, not just in terms of arts as a vehicle for social change, but also the specific issue of addressing mass incarceration. What explains this gravitation?

Wilson hit on a theme previously echoed by Laura Callanan, the founder of Upstart Co-Lab, in our chat on social entrepreneurship and impact investing in the arts. Acting as early adopters, small foundations do the experimental legwork and carve out a space, thereby giving larger institutions the freedom to move in at the time of their choosing:

Foundations like Rauschenberg can take risks and venture into subject matter that may seem too charged for larger institutions, or focus on artists and organizations that are not yet high profile, household names. We can prove a concept and lift up voices in the field deserving of greater investment and larger mics.

"Large institutional funders," meanwhile, "can bring projects to scale. They can marshal a more significant set of resources to actually move the dial on this issue, taking a holistic approach that brings together program officers across issues areas."

Wilson expounds on this sense of scale, noting funders can zoom out and look at "the way rural and urban planning pivot on prison economies, or looking at the impact of incarceration on the health outcomes of communities with a disproportionate number of its families locked away."

Moving forward, Wilson would like to see institutional funders "proactively seek out these internal collaborations, but also partnerships with smaller philanthropies, grassroots orgs and individual donors. These partnerships can more intentionally design initiatives that can begin with R&D led by people on the ground and purposely grow into multi-year, systematic commitments to lower the prison population and shift public opinion of the criminalization of people of color and the poor."

The Artist as a Trojan Horse (and an Idealist)

We next turned our attention to 2017's Artist as Activist Fellows. What common characteristics did these fellows share? I found her perspective on this point to be especially interesting. Typically, artists embed themselves within communities or places like prisons as teachers or speakers. Rauschenberg rejects this role, and instead sends artists off without clearly delineated directives. Here's Wilson explaining something akin to strategic ambiguity:

We have fellows working with advocacy organizations and plugging into larger campaigns to shut down immigrant detention centers and advocate for the rights of immigrant families. But while we frequently describe the artistic outputs of our fellows' projects, we are purposely vague about the change-based strategies they are deploying.

Rauschenberg imagines the fellow as a "Trojan horse, seeming innocuous enough to gain access to spaces and conversations they could not if gatekeepers saw them as anything more than entertainment or an enrichment opportunity for people inside jails and prisons. This is part of their value proposition—they can come sideways and slip under the radar."

Rauschenberg complements this approach with a strong dose of idealism by tapping into what Wilson calls artists' ability to "inspire us to think beyond what we thought we knew in order to realize a whole new set of possibilities."

Wilson called attention to SpiritHouse, a 2017 fellow and collective of North Carolina artists, organizers and community members that are "workshopping NC residents to design a set of cultural practices that eliminate the need for policing as we know it." Here's Wilson:

It is probably impossible to think of a time when we have not had a police force or a culture of punishment in this country. Both are so embedded in American’s expectations of what civil society looks like that for many, the sheer suggestion of a world without police or a world without prisons seems ludicrous. And this is another example of the value artists and cultural workers bring to seemingly intractable issues like this one.

A Holistic Approach

By this point, it should be pretty evident that Rauschenberg's approach to tackling mass incarceration is a holistic one. To that end, Wilson has asked her team at the foundation to talk about the various components at play by describing a "spectrum of change."

Building awareness is on one end of the spectrum (what is commonly referred to as 'changing hearts and minds'); mobilizing people to take action on that new awareness is somewhere in the middle; and then all the way at the other end of creative interventions is imagining a world where mass incarceration doesn’t exist.

At that end of the spectrum, the focus is on "creative problem solving—what are the systems required to eradicate mass incarceration (be they our belief systems or revising the infrastructure used to administer justice)? What are the strategies we need to pursue, not just the tactical plans around specific policy changes, but the larger approach of changing the collective understanding of our social contract with each other?"

Arts philanthropy "can invest not only in awareness building projects, but incentivize the creative problem-solving end of the spectrum." Wilson elaborates:

That means having an expansive definition of art that accounts for design-based practices and cultural work that is about engendering processes rather than products and performances. That means enlisting the expertise of people working in the fields of racial justice and criminal justice to help design programs and assess grant proposals. And the good news is there is appetite across these fields to work together and get at this issue from all directions.

My exchange with Wilson took place before Rauschenberg named Halbreich as its new executive director. That said, given the foundation's commitment to social change and its leadership role within the field of reducing mass incarceration, I don't expect any disruptive changes in the future.

Indeed, Wilson expects Rauschenberg will continue to invest in projects addressing mass incarceration in this next cycle of fellowships, with a particular concern for immigrant detention. The foundation will mount its next call for proposals in January.