Homegrown Help: The Rise of Africa's New Philanthropists

/photo: Aliko Dangote with Bill Gates, and pepsico's Indra Nooyi. photo: Bloomberg global business forum/flickr-CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on April 19, 2018.

In the imagined universe of the blockbuster film Black Panther, the African nation of Wakanda has used the mineral vibranium to build a flourishing society based on advanced technology. A conflict over the purpose of power between two competing heirs to the Wakandan throne drives the film’s narrative. According to T’Challa, Wakanda should prioritize protecting its own people and way of life, while Killmonger dies for his belief that Wakanda should use its power to liberate fellow Africans from oppression.

Although the Black Panther is a fictional Marvel comics character, it is significant that Black Panther is the first popular cultural narrative that imagines an African saving Africans. The film has gotten traction at the same time that a new social class is emerging in Africa: a super-rich elite who are ready to join the ranks of philanthropists trying to help Africans.

The expanding ranks of wealthy Africans can partly be explained by the continent’s high growth rates since 2000. But it is also a result of Africa’s extraordinarily high income inequality, in which 54 percent of the national income is captured by the top 10 percent of earners—the region is now the fourth-highest in terms of income inequality, behind the Middle East, India and Brazil.

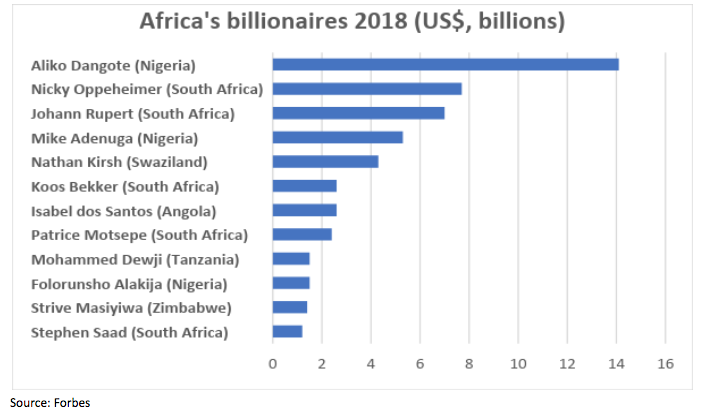

Twelve Africans appear on Forbes’ 2018 list of The World's Billionaires, including Nigerian Aliko Dangote ($14.1 billion, #100) and South African diamond magnate Nicky Oppenheimer ($7.7 billion, #202).

The idea of philanthropy—which emphasizes giving to strangers—is not a well-embedded concept in Africa. As the Sudanese businessman and philanthropist Mohammed Ibrahim put it in an interview with the Financial Times, “This is not because Africans are ungenerous, but because, in many African societies, the notion of an extended family can cover so many people. Cousins of cousins, wives of cousins, wives of cousins of cousins—this tradition of looking after your family is very strong.”

So who are Africa’s top philanthropists, and what are they doing with their money? Well, it is hard to say with certainty, since there is no African equivalent of the Foundation Center, which provides easily searchable data on U.S. foundations by assets and total giving. A recently created organization—the African Philanthropy Forum (APF), an affiliate of the Global Philanthropy Forum—is working to compile and organize this data. According to Executive Director Mosun Layode, many of Africa’s new philanthropists are shy and do not want to publicize their charitable work. However, the Giving Pledge website, media articles, and information provided by the APF offer some insight.

Most Africa-focused policymakers and scholars are familiar with the work of Ibrahim’s Mo Ibrahim Foundation, established in 2006. It has one focus: improving the leadership and governance of Africa. To achieve this goal, the foundation has created and funded the African Governance Index, which measures and monitors governance performance in African countries. It also funds the African Leadership Prize, which awards more than $5 million to a former African head of state who has demonstrated excellence in leadership. The 2017 winner was former Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

Five of the African billionaires on the Forbes 2018 list have created sizeable private or corporate foundations: Aliko Dangote, Nicky Oppenheimer, Patrice Motsepe, Mohammed Dewji and Strive Masiyiwa.

The Dangote Foundation is the corporate social responsibility arm of the Dangote Group—a multinational industrial conglomerate founded by Aliko Dangote in 1981, which manufactures and distributes products like cement, sugar and flour in Nigeria and Africa. According to Devex , it has contributed over $100 million to health and education projects in the past few years. In 2012, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation entered into a strategic partnership with the Dangote Foundation to eradicate polio in Nigeria. In November 2017, the Dangote Foundation announced it would devote $100 million to tackle malnutrition in Nigeria, where protracted Boko Haram violence in the north has undermined food security and created a serious risk of famine.

South African Nicky Oppenheimer and his family created the Brenthurst Foundation in 2004. It essentially operates as a think tank, generating ideas and policy proposals to strengthen economic expansion in Africa. It convenes high-level private meetings to encourage key decision-makers and experts to share insights and experiences. One of the underlying principles of the foundation’s work is that economic growth is the best means to achieve prosperity and political stability.

Another South African mining magnate, Patrice Motsepe, has created the Motsepe Foundation, which is devoted to alleviating poverty and improving the living standards of the country’s poor. It focuses on different sectors, including: education, sports, music, and the arts; religious and traditional organizations; and women’s and gender issues. Some of its activities include funding higher education scholarships, sports leagues and music education at schools, meetings between traditional leaders and government officials, and gender responding budgeting initiatives.

The Tanzanian billionaire Mohammed Dewji has also created a private foundation to focus on three areas: health, education, and community development in Tanzania. Some of the funded activities include the building of rural learning centers that supplement children’s education in STEM fields, support to a children’s cancer ward at a national hospital, and a scholars program to enable outstanding high school graduates to pursue higher education.

Another African billionaire—Strive Masiyiwa from Zimbabwe—was an early pioneer in African philanthropy, creating the Higher Life Foundation in 1996. He and his wife Tsitsi were inspired to create Higher Life when many of the employees at Masiyiwa’s construction firm died of AIDS, leaving behind orphaned children. They invested effort in learning about AIDS orphans by visiting a children’s home in Gokwe, Zimbabwe. This experience led them to fund scholarships for orphaned children to attend primary, secondary and higher education schools. By 2008, as Zimbabwe descended into a humanitarian and health crisis sparked by former President Mugabe’s land seizures, the foundation ventured into health and crisis relief. More recently, it has expanded its grant giving to countries outside of Zimbabwe, such as Burundi and Lesotho.

Just as in the United States, Africa also has corporate foundations not linked to a wealthy individual. One noteworthy example is the Safaricom Foundation in Kenya, established in 2003. Safaricom is a leading telecom company in Kenya, famous for its innovative mobile payment service called M-PESA. The foundation invests in multiple sectors, including health, education, economic empowerment, water, technology, and disaster relief in Kenya. According to its website, since 2003, it has spent about $32 million on philanthropic projects.

As African actors assume more prominent roles on the philanthropic stage, it could transform the strategy and impact of development aid in Africa, giving local civil society a greater say. In fact, the goal of the African Philanthropy Forum is to “promote homegrown development by Africans for Africans.” According to Mosun Layode, “we need to drive change from people who are closer to the problems, who are better positioned to direct resources. You can only go so far with external aid.”

The group is building a network, as well as providing tools and resources to foster a culture of learning among African philanthropists so that their giving can become more strategic, measurable and scalable. According to Layode, Africa has always had a culture of informal giving, but what is new is the effort to institutionalize it and make it more strategic and less ad-hoc.

The bigger picture, here, is that private philanthropy is likely to play a growing role in Africa relative to official development assistance (ODA)—a trend that is also playing out in other regions of the world. According to a new OECD report, although private philanthropy for development remains relatively low compared to ODA, it has become a major partner in specific sectors such as health and education.

As the development community pushes to achieve the Sustainable Development Agenda 2030, will African philanthropists embrace similar priorities and strategies as their western counterparts, or will they generate alternative, “homegrown” solutions? Only time will reveal the answers, for unlike Black Panther, the real story of Africans saving Africans has only just begun.